Tweeting the Enemy: Reimagining Cicero's Feud with Clodius on Modern Social Media

For this blog post, I have focused on the rivalry between Clodius and Cicero, reimagining certain moments described in Cicero’s letters and other sources as taking place on Twitter (now ‘X’).

We must, then, imagine these interactions as set in an Ancient Republican Rome where they happen to have access to modern social media and the internet (and in certain cases, modern slang, emojis, etc)! This creative decision was made in an attempt to balance the modern and ancient elements at play, preserving some of the character and ‘feel’ of the ancient personalities, situations and settings, while placing them in a more recognisably modern format. Events play out in essentially the same way, only here, the Romans can tweet about it. The juxtaposing effect is, I hope, amusing in places.

Making the Fake Tweets

The online interactions were made using websites which allow the creation of customised fake tweets; I used multiple websites for this, as each one offered varying customisation options, and different options were required for each image. I also downloaded some images to add to these tweets (for instance, a ‘profile picture’ for Cicero). All sources for these pre-existing images are listed below.

Characterising the Protagonists

In my characterisation of Cicero, I kept the language generally formal, in keeping with his eloquence, utilizing direct quotes from his letters in some instances. Below, I explain my specific choices more fully in each case. For his username, I simply chose ‘@MTCicero106’, combining his name with the year of his birth to differentiate from any other ‘@MTCiceros’ who may have made accounts before him. For his profile picture, I chose a sculpture of him; an obvious choice, but then Cicero would have surely taken every possible opportunity to brag that he had a statue.

For my characterisation of Clodius, I drew on the image of him as a demagogue.[1] He seemed to have attracted something of a personality cult, similar to today’s supporters of the likes of Donald Trump and Elon Musk.[2] Though Clodius ‘belonged to one of the most illustrious houses in Rome’, he used the ‘non-elite’ pronunciation of his name, and enjoyed considerable popular support as a result of such ‘symbolic gestures of solidarity’.[3] As with Cicero, I explain specific choices in each case, but generally I depict Clodius as more willing to use internet slang, emojis, memes etc., in order to make himself appear more ‘relatable’ to his supporters (as the likes of Trump and Musk do on their social media accounts). I also do not use capitals when typing his messages, as some on the internet tend to do, as a way of mirroring his more ‘rustic’ style (also making him more relatable to his audience).[4] For Clodius’ profile picture, creativity was needed, as there are no (extant) depictions of him. In the end, I thought just as some modern social media users have an image of a character from a favourite TV show as their profile picture, an Ancient Roman equivalent could be an image of a Greek theatre mask. I thought this would also match the ‘relatable’ image Clodius aimed to cultivate. The mask I selected bears a mischievous smile, which further suits Clodius’ character. His username, ‘@therealclOdius’, parallels those of some real celebrities (including Trump) in its assertion that this is the ‘real’ him, and not an imposter; the capitalised ‘O’ in his name emphasises its ‘non-elite’ spelling.

Breaking news, Bona Dea Scandal (Fig. 1)

If Cicero had had access to social media, he would not have had to wait until the Senate convened to publicly give his opinion on news. Furthermore, given how widespread and easily accessed social media is, Cicero’s longing to have Atticus ‘witness [his] wonderous battles’ would be fulfilled.[5] Cicero was boastful and liked an audience, so he would have loved the platform offered by Twitter.[6]

In this image, Cicero is responding to the Bona Dea Scandal. He retweets the news broken by ‘the Roman Times’, and offers his thoughts. I combine Cicero’s own words with Rawson’s description of them.[7] W. Jeffrey Tatum asserts that ‘from the start [Cicero]… believed Clodius was guilty’ and that he felt a ‘sense of public responsibility’ in the face of the incident.[8] Thus, I have depicted Cicero’s response as coming shortly after the news breaks; he wants there to be no doubt as to what his position is on the matter.

‘Wondrous Battles’ (Fig. 2)

On more than one occasion, Cicero shares with Atticus transcripts of recent arguments he has had with Clodius in the Senate.[9] Were these exchanges to have taken place on X [Twitter] instead, Cicero would have simply been able to take a screenshot and share that with Atticus via a direct message - as depicted in Fig. 2.

The argument he shares is a more or less exact reproduction of that from Walsh’s translation of Att. 2.1.5. The messages which precede and follow the screenshots are mainly of my own composition, though borrowing some phrases from Att. 2.1.3-5, and one of Cicero’s nicknames for Clodius from Att. 1.16.10.

Clodius kicks Cicero while he’s down (Fig. 3)

This interaction takes place sometime during Cicero’s exile. Letters to and from his loved ones sustained him during this period[10] and if he had had access to modern social media, these connections would have been much more readily available.

This is not all that would have been readily available to Cicero. In Q.fr. 1.3.5, Cicero asks his brother Quintus to let him know what the situation is like in Rome, for of course, Cicero cannot check himself. With access to X [Twitter], however, he could have monitored the state of affairs himself somewhat by checking what sort of things people were posting.

Not everything being posted would have been helpful to Cicero, however, owing particularly to his grief, homesickness, and generally poor mental health during this period. Fig. 3. depicts one such post Cicero would certainly not have wanted to see: a Tweet by his ‘arch-nemesis’ Clodius, gloating over the destruction of ‘the grand mansion… of which Cicero had been so proud’.[11]

I depict Clodius sharing a meme based on the popular ‘Disaster Girl’ template, part of his attempts to appear relatable to his followers. Aware of the power of social media to attract popularity, he has given his supporters a nickname, and uses hashtags. Clodius encourages his followers to engage with him to make them feel on a level with him, despite the vast discrepancies in status and power which in reality exist between them. To Clodius’ personality cult, he can do no wrong. They are an online equivalent to the mobs that rallied around him.[12]

When Cicero sees this post, his pride spurs him to respond, hoping to shame Clodius for sharing such a mean-spirited meme, and to save face when confronted with people making fun of his misfortune. Because this (obviously) never happened, Cicero’s words here are entirely my own. I tried to match his general style of speech, and included a quote from Homer (Odyssey 8.328) emphasising his point, as Cicero sometimes did.[13]

Unfortunately for Cicero, Clodius has a screenshot of a similarly distasteful joke ‘[unworthy] of a consul’ which Cicero had made some time before.[14] In our reality, Cicero made this joke during a private conversation with Clodius (as he shares with Atticus in Att. 2.1.6), but on social media, the lines between private and public are blurred; all it takes is a screenshot for a ‘private’ direct message to become public.

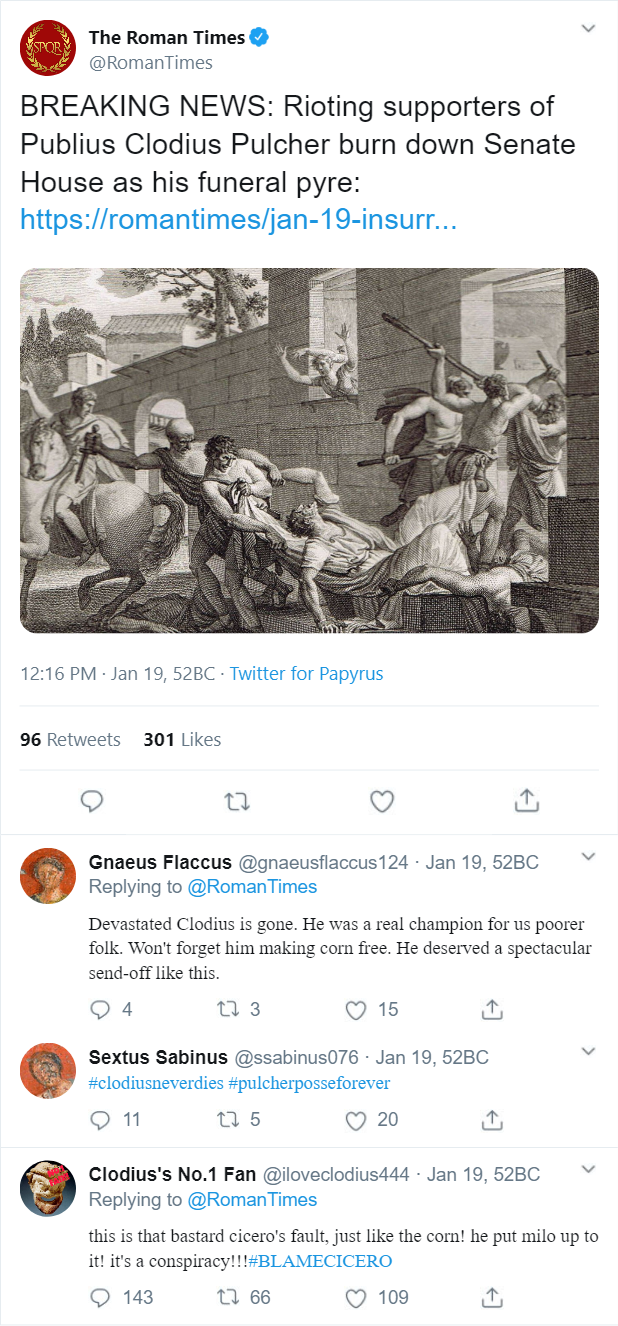

Clodius’ Online Mob (Figs. 4 and 5)

Fig. 4. (left) shows an online reimagining of Clodius riling up a crowd by blaming high corn prices on Cicero’s return.[15] Finally, Fig. 5 (right) depicts a news headline following the burning of the Senate House by Clodius’ followers, along with some of his supporters’ responses; as in our reality, Cicero is blamed again.[16]

The burning of the Senate House by Clodius’ followers (unable to accept his death) eerily mirrors January 6th 2021, when Trump’s supporters (unable to accept his loss of the election), attacked the U.S. Capitol.[17] Indeed, when a public figure commands a personality cult, an online mob can become a real one dangerously quickly.

Jesse Tobias Dent Gallagher (he/him) is a final-year student of Classics and English at Trinity; this blog started life as an assignment for the module Social Media in the Ancient World (CLU33212), taught by Professor Anna Chahoud. Jesse is currently working on the second draft of his first novel, and hopes to write professionally some day. Ironically, he doesn't use social media very much.

Footnotes

[1] Rundell, W. M. F. ‘Cicero and Clodius' pp. 301–2.

[2] See for example Ben-Ghiat, ‘Trump’s Formula’ and De Vrie, ‘Elon Musk’.

[3] Rawson, Cicero: A Portrait, p.94; Riggsby ‘Clodius/Claudius’, pp.120-122.

[4] See for example Joho, ‘embrace the lowercase’; Riggsby ‘Clodius/Claudius’, p.122.

[5] Cicero, Att. 1.16.1.

[6] See for example Cicero, Fam. 5.12.

[7] Cicero, Att. 1.16.1; Rawson, Cicero: A Portrait, p.95.

[8] Tatum, ‘Bona Dea Scandal’, p.208.

[9] See for example Cicero Att. 1.16.9-10, Att. 2.1.5-6.

[10] See for example Cicero Att. 3.7, Q.fr. 1.3.

[11] Riggsby, ‘Clodius/Claudius’, p.117; Rawson, Cicero: A Portrait, p.116.

[12] See for example Cicero Att. 4.3.

[13] See for example Cicero Att. 2.5, 2.9.

[14] Cicero Att. 2.1.16.

[15] Rawson, Cicero A Portrait, pp.122-123.

[16] Ibid., pp.113, 137-139.

[17] See for example Duignan, ‘January 6 U.S. Capitol attack’.

Bibliography

Ben-Ghiat, Ruth. ‘Op-Ed: Trump’s formula for building a lasting personality cult’. Los Angeles Times, 9 Dec. 2020. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2020-12-09/donald-trump-strongman-personality-cult Accessed 28/04/2023.

Cicero, Marcus Tullius. Selected Letters. Translated by P.G. Walsh, Oxford University Press, 2008.

De Vrie, Quincy. ‘The Cult of Personality of Elon Musk’. The Orwell Society, 2022. https://orwellsociety.com/bursary/2022-winning-submission-the-cult-of-personality-of-elon-musk-by-quincy-de-vries/ Accessed 28/04/2023.

‘Disaster Girl’. Know Your Meme, https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/disaster-girl Accessed 29/04/2023. (Used as template for Clodius’ meme in Fig. 3.)

Duignan, Brian. ‘January 6 U.S. Capitol attack’. Encyclopedia Britannica, 28 Apr. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/event/January-6-U-S-Capitol-attack Accessed 29/04/ 2023.

Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by E. V. Rieu, Penguin Books, 2003.

Joho, Jess. ‘the surprising reasons we turn off autocaps and embrace the lowercase’. Mashable, 4 Aug. 2019. https://mashable.com/article/disable-auto-caps-lowercase-texting-online-communication Accessed 28/04/2023.

Rawson, Elizabeth. Cicero: A Portrait. Allen Lane, 1975.

Riggsby, Andrew M. ‘Clodius / Claudius.’ Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte 51(1), 2002, pp. 117–23.

Rundell, W. M. F. ‘Cicero and Clodius: The Question of Credibility.’ Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte, 28(3), 1979, pp. 301–28.

Tatum, W. Jeffrey. ‘Cicero and the Bona Dea Scandal.’ Classical Philology, 85(3), 1990, pp. 202–08.

Sources for images

Digital Reproduction of Silvestre David Mirys’ Death of Clodius. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clodius_killed.jpg Accessed 29/04/2023. (Used as headline image in Fig. 5)

Picture of a Greek Theatre Mask. The British Museum, http://www.teachinghistory100.org/objects/about_the_object/greek_theatre_mask Accessed 29/04/2023. (Used as Clodius’ profile picture and that of his fan in Figs. 2-5)

Photograph of a Bronze Statue of Julius Caesar in Rome. Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Julius-Caesar-Roman-ruler#/media/1/88114/228404 Accessed 29/04/ 2023. (Used as headline image in Fig. 1)

Photograph of a Sculpture of Cicero. National Geographic, https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/cicero/ Accessed 29/04/2023. (Used as Cicero’s profile picture in Figs. 1-3)

Photograph of a Statue of Cicero in Rome. Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/da917bd2-3e22-4f67-8975-bd609756ba19 Accessed 29/04/2023. (Used as headline image in Fig. 4)

Photograph of a Wall Painting from Pompeii. History Hit https://www.historyhit.com/togas-and-tunics-what-did-ancient-romans-wear/ Accessed 29/04/2023. (Used for the profile pictures of Clodius’ supporters in Fig. 5)

SPQR Image. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SPQR_sign.png Accessed 29/04/2023. (Used as the Roman Times’ profile picture in Figs. 1, 4, 5)